tw: eating disorders

DISCLAIMER: I AM NOT A MEDICAL PROFESSIONAL. PLEASE DO NOT USE THIS AS A SUBSTITUTE FOR PROFESSIONAL MEDICAL ADVICE!

This is the second part of “IBS: How Capitalism Cooked Up a Whole New Disease”. Part I

It’s All Coming Together

Last time I wrote on how capitalism planted the seeds for Irritable Bowel Syndrome, or IBS. As a reminder, IBS is a catch-all term for many gut-related issues. It’s not a disease with a cure (like celiac disease), because it covers a whole range of possible causes. This makes an IBS “diagnosis” particularly frustrating.

While IBS has many symptoms, two dominate: gas overproduction and poor motility (faulty transit of food through the gut). These usually manifest in the forms of painful bloating, constipation and/or diarrhea. The canonical IBS symptoms often feed off of each other, with each problem making the others worse over time.

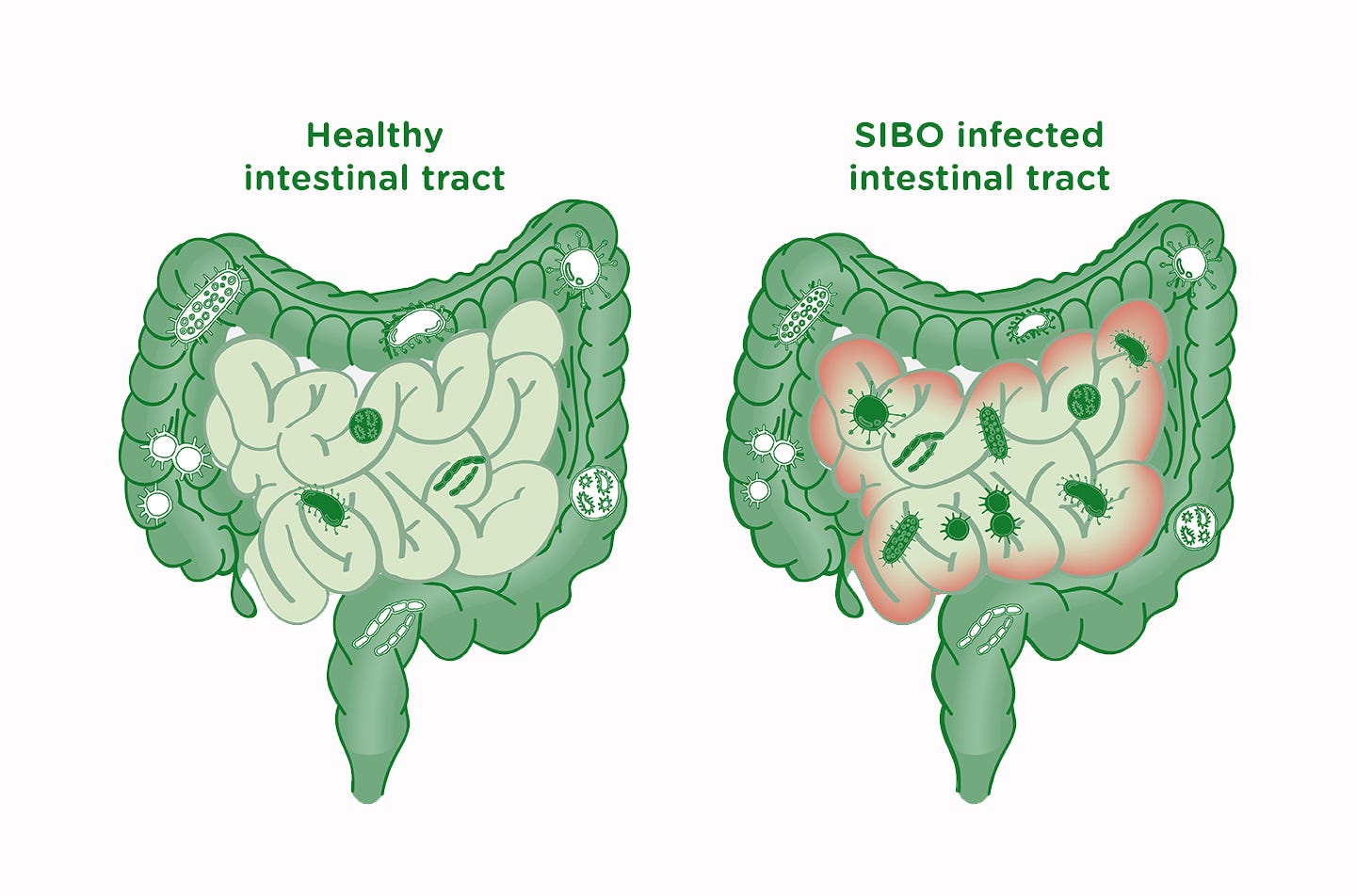

Scientists are still unsure what causes IBS, but they generally blame system shocks—natural stimuli that affect the routine process of digestion. The two relevant systems are the nervous system (responsible for motility) and the microbiome (gut bacteria responsible for gas-producing digestion).

Nervous dysfunction is usually blamed on poor sleep, chronic stressors, and other disruptions to bodily rhythms. Microbiome dysfunction is usually blamed on food additives, high sugar intake, and eating at very late hours. There is also mounting evidence for the existence of the “gut-brain axis”, the idea that nervous dysfunction drives microbiome dysfunction and vice versa.

If you combine this info with the trends from my last article, then you can see it all coming together. Even without the full biological picture, we can already see the outlines of a causal relationship between capitalism and these IBS system shocks.

But no matter how widespread a set of symptoms is, it still needs something else to become anything more than a set of symptoms. This critical “something else” was nutrition-as-lifestyle, a mindset that created the conditions for IBS to emerge as a coherent label. Once a label gains enough cultural relevance, disease status becomes all but inevitable.1

Anti-Lifestyle Marketing

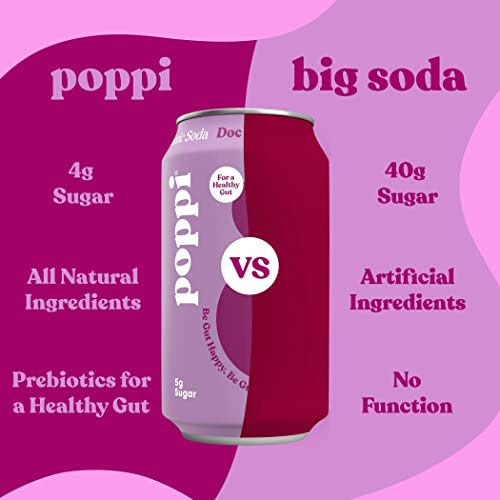

Traditional lifestyle marketing builds a lifestyle around a specific type of consumption (like drinking a soda). But modernity has produced anti-lifestyle marketing, which builds a lifestyle around a specific lack of consumption (like not drinking a soda). Hate the soda industry? No problem! You can consume around your aversion to soda instead.

This ability to bring anti-consumerism back into the consumerist fold is one of capitalism’s greatest strengths. In this way, even anti-capitalist sentiment can be made to serve the goals of the capitalist system.

Anti-lifestyle marketing has mainstreamed dozens of popular diets, which each have entire marking ecosystems around them. This is not to say that these diets are without merit, but simply that they are prime targets for marketing departments!

Veganism represents compassion, progressivism, and environmental consciousness. The carnivore diet represents simplicity, conservatism, and a desire to return to primal roots. What kind of lifestyle does IBS represent?

Since IBS is newer, its identity is still in flux. However, the branding that has gotten the most traction is IBS as a “hot girl” phenomenon. Advertisements for IBS tend to use bright colors, positive imagery, and affirming language.

The optimistic reading of the trend is that it puts a positive spin on gut health, which allows people to talk about it openly. Just like somedays uses a period pain simulator to raise awareness about endometriosis, proponents of “hot girl IBS” argue that it will make unaffected individuals (especially men) more likely to believe their concerns.

However, another possible reading of hot girl IBS is far darker. In the wake of greater eating disorder awareness, companies don’t have quite the same license to use sneaky marketing tactics. But many of the tropes that drove skinny lifestyle marketing and thus eating disorders are still present in IBS marketing— replace “low-calorie” with “low-FODMAP” and similarities start to emerge. Could IBS simply be an attempt to sanitize the eating disorder mindset into a more socially acceptable form?

IBS Imagined as Bulimia 2.0

While IBS and eating disorders occupy a similar space in the discourse, they are rarely mentioned in the same breath. But maybe they should be, because the share of eating disorder sufferers who developed a disease like IBS later in life is a shocking 98%.

Scientists have hypothesized that the erratic food intake present in eating disorders may lead to dysmotility and even microbiome issues. Of course, you can still develop IBS without an eating disorder! But it’s kind of like the relationship between smoking and lung cancer— non-smokers can still get it, but smokers at a way higher risk. This hypothesis would also conveniently explain the IBS gender gap.

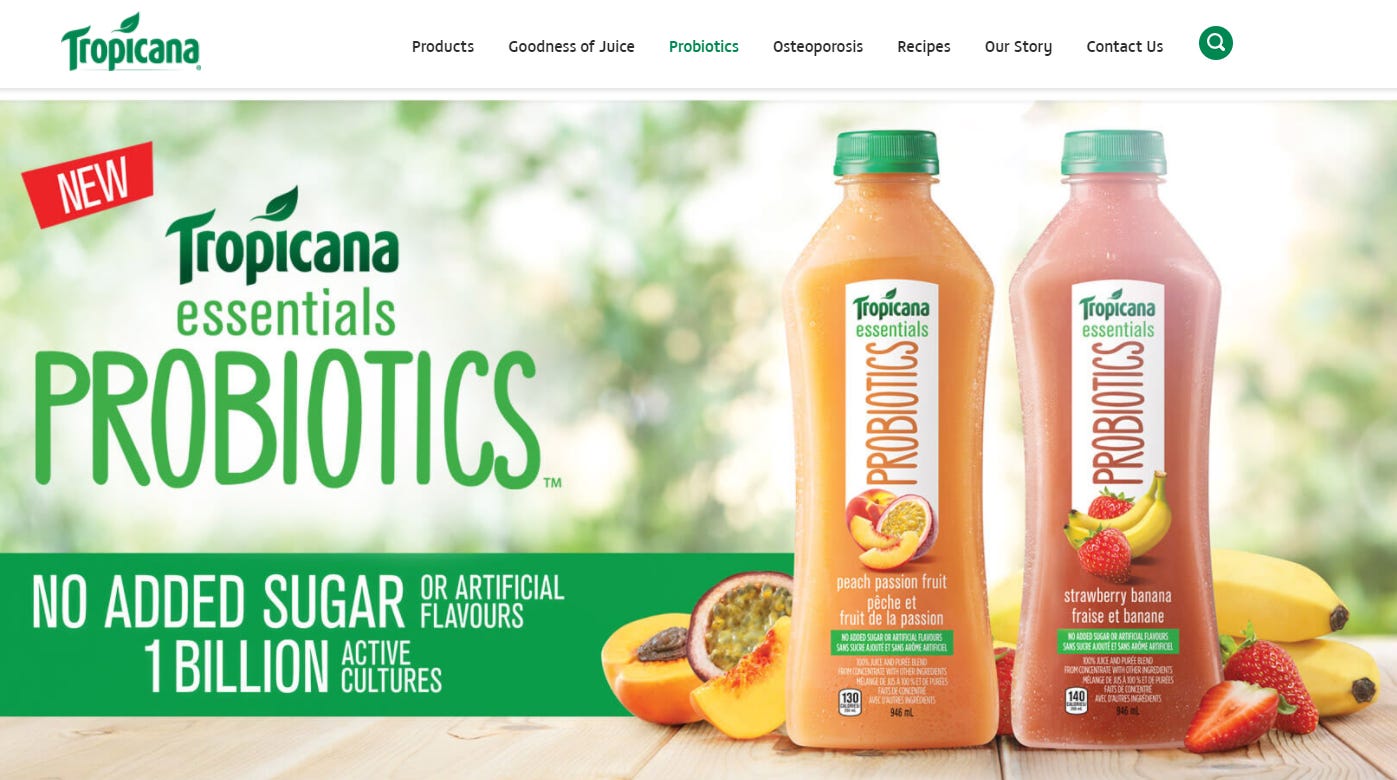

The connections don’t end there, as IBS and eating disorders have many similar associations. One such association is marketing. Just like the weight loss industry sells “miracle cures”, so too does the budding gut health industry. The probiotics of today echo the detox teas of yesterday. Probiotics may have more of a scientific basis, but the mono-strain varieties used in food additives have shown inconclusive results.

IBS discourse is also similarly peppered with purity language, encouraging people to consume good, clean essences while avoiding dirty, bad essences. These evaluative labels are everywhere: the gut health industry touts the importance of “good bacteria” outnumbering “bad bacteria”, and certain irritants are called “problem foods”.

These IBS judgements are not uniform, meaning that many people remove foods from their diet entirely with no real scientific basis. A common refrain is “I can’t eat apples / beans / bread. My body just can’t tolerate it. Everyone’s body is different!”.

While more diversity in medical advice is sorely needed, taking a hacksaw to your diet like that is rather hasty. The idea that some people can’t even able handle an apple because of how they were born betrays a real lack of confidence in the human body. Early humans were fine eating all sorts of stuff!

But these arbitrary personal purity standards may become a point of personal pride as an IBS sufferer sinks deeper into the IBS lifestyle. And if someone has bad enough associations with a certain food, then that in itself could make it more difficult to digest! The nocebo effect and the gut-brain axis make a powerful team.

Some people go even further by trying to exorcise supposed dirty essences from their body. A “colon cleanse”, an alternative medicine practice that shoots water into your large intestine, seems to rhyme with a bulimic purge. Another popular “deep clean” is rifaxamin, an antibiotic meant to wipe out all the bad bacteria in the gut (along with the good bacteria). This treatment has shown some promising results, but you have to wonder how many people are taking it as an exercise in purity.

To be clear, IBS is sparked by true biological unhealthiness, unlike eating disorders. The pain experienced by a dysfunctional gut is far more than just social construction. But we should be mindful about IBS discourse going off the rails! As we will soon see, an extreme attitude towards IBS can even get in the way of treating the issue itself.

Case Study: Shreya’s IBS Nightmare

“Okay, so IBS may have an uncomfortable relationship with eating disorders,” you say. “But aren’t IBS restrictions actually based in science?”2 Well, yes! But IBS discourse is uniquely susceptible to the reduction problem, which is when nuanced ideas break down at scale. IBS ideas start out scientific, but they end up turning into memetic slop. Because of this, sufferers usually come away with more questions than answers.

In order to understand how this happens, let’s walk through a hypothetical. Shreya is a young woman who goes to her family doctor after developing digestive issues. Her doctor diagnoses her condition from a motility perspective, because poop questions are much easier than gut gas analysis. The three different motility diagnoses are:

IBS-D: there is something wrong with your gut that is making you poop too much

IBS-C: there is something wrong with your gut that is making you not poop enough

IBS-M: there is something wrong with your gut that is making you poop sporadically

Shreya gets diagnosed with IBS-C. Since IBS-C is a constipation diagnosis, Shreya is instructed to take a bunch of fiber, laxatives, and water over several weeks. The idea is that the fiber will push through her body undigested, stimulating motility. Fiber will also feed her microbiome, helping to maintain a healthy ecological balance.

When Shreya gets home, she buys a big jar of Metamucil gummies and takes them as instructed. However, this causes her to experience far more pain and bloating than ever before. She tries to follow her doctor’s instructions, but the discomfort eventually becomes too much to handle. She books another appointment in a couple of months.

Shreya returns to the doctor and explains what happened. The doctor explains that some people react badly to fiber, so she should consider taking a different type of fiber along with a stool softener like Colace. Shreya is too scared to touch fiber again. The stool softener does help her constipation, but she still feels awful after every meal.

Still frustrated and six months out from her next appointment, Shreya turns to the Internet for answers. She reads about elimination diets, which involve cutting out all potential “problem foods”. Reddit tells her to avoid “FUDMAPs”, or something like that. She doesn’t totally get what they’re saying, but she does know that cutting out all these foods has made her feel better than she’s felt in a long time.

After hours of reading forums online, Shreya becomes convinced that she has Small Intestine Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO), a rare microbiome disorder. Users advise her to be aggressive about treatment, since most doctors will just get in your way. After acquiring this new knowledge, Shreya feels prepared for her next appointment.

Shreya’s doctor tries to explain that SIBO is an extremely rare condition, but Shreya isn’t having it. She asks to be prescribed rifaxamin, the aforementioned antibiotic that kills all your gut bacteria. Furthermore, she demands to get a biopsy to test for SIBO.

Her doctor reluctantly agrees. Shreya takes the rifaxamin, but her symptoms don’t improve; if anything, they get worse. By the time she tests negative for SIBO, Shreya is dismayed and confused. On the forums, users reassure her that she could still have SIBO, and most doctors don’t really know what they’re talking about anyway.

After a couple more bad episodes with various produce items, Shreya decides to make her heavily restrictive diet permanent. She’s not happy about giving up so many foods she used to love, but it’s better than being in constant pain.

So what happened? Why did Shreya have such a miserable experience?

Shreya’s 1st Problem: IBS Isn’t Just One Thing

This story wasn’t meant to shame Shreya or anyone like her. Going into the doctor’s office with a plan is always a good idea. I was primarily trying to illustrate how an IBS downward spiral often pulls patients into a vortex of pseudoscientific ideas.

The biggest weakness of the standard treatment is that it fails to communicate what is actually going on. IBS is a multifaceted condition, and the amount of nuance make it challenging to fully explain. On the other hand, pseudoscience provides quick, black-and-white answers in the form of “this food good, this food bad”.

For example, bloating and bad motility in IBS are related yet different problems that may require different kinds of treatment. As with cancer, addressing the problems caused by the condition is different from the condition itself. Some things that help your microbiome end up hurting motility and vice versa.

Even when doctors try to communicate this, it often falls on deaf ears. People who are in serious pain every day and can’t poop don’t want to hear something like this— they want immediate relief! Since restoring your digestive rhythm is a long process that comes in fits and starts, taking a hatchet to your diet can be a lot more appealing.

Finally, motility-focused cures like laxatives are rather indirect and often insufficient for addressing bloating on their own. Patient gets frustrated when their prescribed treatment doesn’t directly address their primary concern, even if it will supposedly help out in the long run. All of these factors draw the Shreyas of the world into the Internet wilds, searching for something more.

Shreya’s 2nd Problem: Fiber is a Black Box

So why did Shreya start having problems in the first place? Doesn’t fiber address both issues: motility and the microbiome? Why did it cause her so much grief?

Fiber has long been a staple of dietary advice, as scientists have consistently found that Americans don’t eat enough fiber. Because of this, it has long been a staple of nutrition-as-lifestyle marketing, bringing to mind healthy lives, clean bodies, and a generally healthy essence.

But fiber isn’t a single thing. There’s insoluble fiber, which is the element that pushes through the intestines undigested. But there’s also soluble fiber or prebiotic3 fiber, which is digested by the microbiome. You may have noticed this contradiction earlier: how can fiber be digested by the microbiome if it goes undigested? But we usually don’t allow our thought process to get this far because of that elemental mindset.

This “fiber illiteracy” runs deep. I picked up a jar of fiber supplements just the other day that said “Fiber is not digested, thus has no caloric effect” on the bottle. While the caloric part is at least debatable, the digestion part is just straight up incorrect!

Despite being thought of as One Essence, fiber is really multiple substances playing multiple roles. This reality is often not effectively communicated to the patient, which makes “just take fiber” all the more mysterious and suspicious.

But that’s fine, right? Won’t more fiber help regardless, since it has healthy effects on the microbiome and motility? Not necessarily! This idea of fiber as unqualified Good is a product of our nutrition-as-lifestyle programming.

What if I told you that all fibers are carbohydrates? It is one of the three types of carbs: sugars, starches, and fibers. If you’re more biologically inclined, then this may not come as a surprise. But for most Americans, this doesn’t track with the Carbs = Bad Fiber = Good world that we live in.

It’s important to understand that fiber is not always good, especially in the context of IBS. Soluble fibers in particular can cause gas, since microbiome digestion is what causes gas in IBS. And while insoluble fiber is good for motility, too much of it at once can clog up your whole digestion system. So fiber is good for motility and the microbiome, but it can also produce those dreaded symptoms. Think of how putting alcohol on a cut hurts even though it’s necessary in the long-term!

Since fiber can make patients feel way worse, the standard IBS treatment starts out already on thin ice. Many gut health blurbs try to duck away from this dissonance, saying nonsense like “it supports healthy gut flora balance and regular bowel function without harsh fibers like psyllium”. In other words, Fiber Good but some Fiber Bad.

But it’s not so easy to draw this distinction, since responses vary a lot depending on the person. And the fiber that tends to be the best for your microbiome is often the worst for gas. Even a healthy microbiome produces gas when exposed to beans— gas means that your microbiome is feeding! This gives IBS patients confusing signals— is this gas a sign of progress? Or a serious setback? The longer this treatment takes, the more sufferers question whether all of this fiber is doing them any good at all.

Shreya’s 3rd Problem: FODMAP Makes No Sense

As mentioned before, elimination diets are far more effective than other treatments at providing instant relief. This is because instead of trying to ensure long term gut health (which is hard), they simply remove the stimulus (which is easy).

While elimination diets are the preferred method of online IBS communities, they are also sparingly prescribed by doctors due to their quick results. In many cases, a break from the pain is enough to restore rhythm to the digestive process.

However, doctors add the all-important caveat that elimination diets are supposed to be temporary. They are primarily meant to calm the digestive system down. After that, most if not all of the foods can be added back in.

I’d like to be very clear: eliminating “problem foods” alone doesn’t do anything to fix IBS! If you never add the foods back in, then all you’re doing is avoiding the problem!

But nevertheless, the “add stuff back” step often gets lost in reduction. And I can’t really blame people for this. If adding back foods make you feel worse (even if only a bit), it’s a lot easier to just say “Beans = Bad” and call it a day.

Beans are part of the most notorious group of “problem foods”, collectively known as FODMAPs. (This word has already made a couple of cameos in this post.) FODMAPs are singled out for their propensity to cause gas, but they are classified by the specific role they play in digestion.

What role, you ask? This is where we’d expect the acronym to help us out. Maybe each letter of FODMAP represents a different food group? Or maybe it’s shorthand for some scientific term? Unfortunately, FODMAP is just an unhelpful aesthetic disaster:

Fermentable

Oligosaccharides

Disaccharides

Monosaccharides

And

Polyols

Even a quick glance should tell you that this acronym is deeply wrong. The F stands for fermentable, an adjective. And it’s not even clear what “fermentable” applies to: are only the oligosaccharides fermentable? What about the polyols? The inclusion of “And” is just icing on the cake. (I get that they needed vowels, but come on.)

Not only that, but these broad categories add little information. Oligosaccharides is a huge category, but FODMAP only refers to a small part of it. The official Monash website gets a bit more specific: FODMAPs are fructans, galacto-oligosaccharides, lactose, fructose, manitol, and sorbitol. In other words, FODMAP gets us from 6 items to 4. Couldn’t this scheme have been consolidated?4

But my real gripe with the FODMAP acronym is that it buries meaning. There’s a common word that encompasses monosaccharides, disaccharides, oligosaccharides, and polyols: carbohydrates.5 Why don’t doctors just say fermentable carbohydrates? This phrase actually carries meaning, unlike the buzzword that is FODMAP.

Because fermentable gets at the heart of what’s really going on in IBS. In school we’re taught that food is broken down in the stomach and absorbed in the intestines. We can break down most of our foods with enzymes, which allows us to absorb them in the small intestine. But we tend to gloss over the next part: if we don’t have enzymes for some food, then it gets fermented by the bacteria in our gut.

Fermentation produces gas, and essentially all gas production can be traced back to the fermentation process. This is why black beans cause farts and rice doesn’t. Rice is mostly made up of amylose starches that can be broken down by amylase, while black beans contain nutrients like raffinose and stachyose that don’t have a natural enzyme.

This is not a bad thing! The rest of your body co-evolved with its gut bacteria, meaning that its behavior takes this process into account. But in some cases, fermentation can cause problems. For example, a lack of lactase enzymes leads to lactose fermentation, which creates a lot of gas. This is what causes most lactose intolerance.

Again, this is not because FODMAPs have “bad essences”. It’s just because FODMAP digestion is the first thing to go when your body falls out of its digestive rhythm. Just to drive this home, I’ll add that the all-important soluble fibers are FODMAPs! Okay, not every soluble fiber is officially a FODMAP. But a couple (like inulin and wheat dextrin) definitely are.

In this Ask a Geneticist column, Dr. Barry Starr explains how competition between bacteria in your gut can drive food intolerances. An ability to digest milk gives milk-digesting gut bacteria a competitive advantage, but this can become a liability if the milk goes away. While enzymes themselves are not “use it or lose it”, your gut bacteria can still get out of the rhythm of properly fermenting certain foods.

So it’s not just that eliminating FODMAPs doesn’t fix the problem. In Shreya’s case, it may have actually made it worse (especially after she nuked her gut with rifaxamin)! Removing all those foods from your diet is bad news for your gut in the long run.

Conclusion

In the end, Shreya was caught between massive biopsychosocial currents that she had little hope of protecting herself from. This led her down an unfortunate path that did a number on her institutional trust. She might never trust doctors the same way again.

Unfortunately, Shreya’s story is a common one, one that repeats across the Internet every day. IBS and SIBO forums are full of people who start out skeptical or lost and become depressed. These people describe symptoms so severe that they may very well be out of modern medicine’s reach. But most people who read about IBS have far more mild conditions, and I’m afraid of it convincing them that their condition is incurable.

Because hope is just so important when it comes to illness. The brain-body divide is less clear than you might think. I don’t mean to say that IBS is imagined or made up; rather, I want to emphasize that despair causes physical suffering that is true and real.

So what should people in Shreya’s situation do? Even if they know this, they can’t just manifest the pain away! Well, they should at least be open-minded to a change in their condition! If something was a “problem food” once, that doesn’t mean it will still be one a year later! Foods don’t have permanent “bad essences”, and IBS doesn’t have to be a permanent diagnosis. But if you cook a bit too hard, it very well could be.

There are also many treatments like fiber, laxatives, enzymes, stool softeners, and other supplements that can make IBS symptoms more tolerable at the margins. These are useful not just for accidental FODMAP ingestion but also for diversifying your diet. Eating more kinds of produce is probably the best thing you can do for your gut.

That being said, IBS sufferers who want to get better will have to “embrace the suck” sometimes. I worry that sufferers will retreat at the first sign of gas, traumatized by their early digestive experiences. While this trauma is worthy of respect (especially alongside a history of eating disorders), we must remember that FODMAP digestion always produces a bit of gas, even for healthy patients. A little bit of gas shouldn’t scare us away from all the foods we love.

What about everyone else— the people who have not yet developed IBS? Many people with similar ideas about food have turned to the Pollan diet, which is summarized in the following pitch:

The most sensible diet plan ever? We think it’s the one that Michael Pollan outlined a few years ago: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” So we’re happy that in his little new book, Food Rules, Pollan offers more common-sense rules for eating: 64 of them, in fact, all thought-provoking and some laugh-out-loud funny.

By “food” Pollan means real food, not creations of the food-industrial complex. Real food doesn’t have a long ingredient list, isn’t advertised on TV, and it doesn’t contain stuff like maltodextrin or sodium tripolyphosphate. Real food is things that your great-grandmother (or someone’s great-grandmother) would recognize.

Pollan points out that populations that eat like modern-day Americans — lots of highly processed foods and meat, lots of added fat and sugar, lots of refined grains — suffer high rates of obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and cancer. But populations that eat more traditional diets don’t. Our great-grandmas knew what they were doing.

This is great advice for the majority of Americans, as it avoids those risky additives and sugar bombs that cause most of our dietary woes. But I am still skeptical of the motivations behind the Pollan diet. Many who adopt such diets fancy themselves as all-natural, proudly weaving them into their identities. They decry the evil essence of modernity, while the natural essence represents all that is Good.

To me, this attitude is a capitulation. Just as I don’t like nutrition-as-lifestyle, I’m no fan of nature-as-lifestyle either. I’m suspicious of any effort to form a lifestyle around a lack of consumption. It reeks of the same dogmatic stench that gave us all of these problems in the first place.

Furthermore, are we really going to run away from all the knowledge dietary science has given us? I want human diets to become better, not regress to the ways of our ancestors! If we start talking about “natural essences”, then we’re back to the same pseudoscience that we started off with. We should give tradition its due, but we shouldn’t just admit inferiority to our pre-industrial ancestors.

Remember, the root of all this evil isn’t artificial food at all. When our ingenuity is directed towards improving human nutrition, there have been incredible benefits. The “evil essence” is the unholy collision of food and marketing, which incentivizes us to stray away from that which is Good. The promise of natural food isn’t their “natural essence”, it’s the lack of ruthless engineering meant to hijack your reward pathways.

My advice would be simpler: if you want to eat healthy food, stop playing the game. Eat food because you already wanted it, not because some brand is pitching it in a shiny package. If someone is selling addictive crunchiness without the fat, be skeptical. If someone is selling weight loss without the discipline, be skeptical. If someone is selling sweetness without the sugar, BE ESPECIALLY SKEPTICAL.

Just remember that Sardinian grandmas have done just fine without counting calories, FODMAPs, or macros. Do you really need a fad diet to tell you that the snack aisle is bad for you? Don’t let the siren song of marketing distract you from what you already know to be true.

Because being healthy doesn’t have to be that much of a grind. You need not punish yourself as penance for your dietary sins. Foods can’t stain you with any kind of evil essence, no matter how much nutrition-as-lifestyle marketing tries to convince you otherwise. A suboptimal diet isn’t the worst thing in the world— it’s just suboptimal! And a diet that is suboptimal for your health may just be optimal for your soul.

It’s worth mentioning that most weight loss diets are also based in science. Eating super caloric foods all the time is obviously not healthy! It’s just that pathological avoidance is also bad. So this may be the wrong question to ask— even scientifically-backed behaviors can have unhealthy consequences!

This is a bit of an oversimplification, as prebiotic fiber technically has to be linked to a certain “good bacteria”, while soluble fiber just has to dissolve in the body. But it works well enough as a mental model!

A modest proposal: combine manitol and sorbitol into (sugar) alcohols. (Alcohol isn’t great for IBS anyway.) Consolidate fructose and fructans into the same category to emphasize fructose malabsorption. Already you have the much nicer FLAG:

Fructans + Fructose

Lactose

Alcohols

Galacto-oligosaccharides

Again, this is a bit of an oversimplification— resistant starches are non-FODMAP fermentable carbohydrates (fermentable polysaccharides), and FODMAP technically only refers to specific fermentable carbohydrates. Nevertheless, “fermentable carbohydrates” is way more legible than FODMAP. Resistant starches bother some people with IBS anyway!

Both informative and funny; I laughed several times. Good job