Nuance and the Reduction Problem

“What if someone takes it out of context?”

—Everyone with a platform, ever

Modern online discourse suffers from the fact that any viral message is at great risk of being reduced to its most viral form. This is because more viral interpretations will spread faster than less viral ones by definition. Even though an interpretation’s validity has a slight impact on its virality, that impact is small. The interpretation’s effect on primal emotions, like fear, disgust, and rage, is far more important.

So if your message comes with an easy misinterpretation that is far more viral, you should expect that misinterpretation to be a large share of that message. This has broad implications for how we choose to convey truth. My intuition is that spreading a reduction-proofed message is more important that conveying maximal nuance.

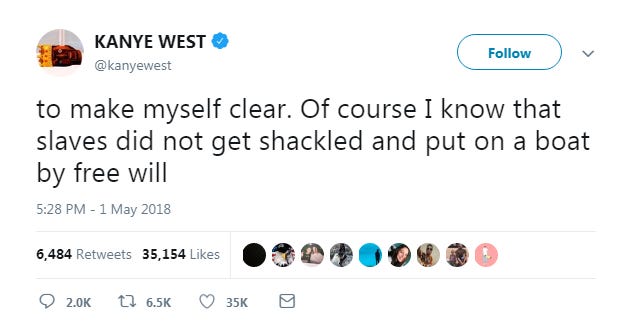

It might seem irrational to sacrifice nuance for a lower risk of misinterpretation. But I would argue that most people share this intuition, at least on the extreme end. Take Kanye West’s statement, “Slavery is a choice”. Kanye was trying to make the point that the mental shackles of slavery were more important than the physical shackles: slaves theoretically had the numbers to overthrow their owners, but they were held back by the identity of subservience drilled into them since birth. This is an interesting point, one with the potential to start a heady late-night conversation. But almost everyone agrees that you can’t just say what Kanye said! It’s just too susceptible to reduction for productive online discourse.

Not only does reduction limit the public’s access to truth, but it can also harm causes that the original message was trying to push. For example, many messages in critical theory have been reduced such that the public is now resistant to their conclusions. I acknowledge the existence of systemic racism: that is, racism was such a key part of pre-1960s American law that even an America without that explicit racism will still produce racist outcomes. However, this does not mean that I believe all black people are structurally disadvantaged by racism in the same way, or that our institutions are fundamentally racist. This is also acknowledged by critical race theory: the main point of critical race theory is that all racial issues deserve to be examined by more nuance than just “people face racist outcomes when people are being racist”.

But the nuanced claim “a complex interaction between the racially unequal aspects of society in the 1960s, the biases people absorb by living in such a society, and a number of overtly racist interactions produces racist outcomes” is less transmissible than the reduction “institutions produce racist outcomes, so people in them need to stop being racist”. Since this message rings false to most of the public (most Americans believe that they are not consciously racist), it makes them less receptive to the constructive aspects of critical race theory and its implications. I would argue that critical race theory was not sufficiently “reduction-proofed” before it spread to the public.

Now this in itself is a bit of a simplification: it’s not like there was some “critical race theory PR team” that got together and agreed on a cohesive message to export to the general public. These things are messy, and academics don’t have a ton of control over how their ideas spread. But the message that emerges is the sum of every individual messaging choice. And some of these individual choices clearly contributed to the reduction problem.

For example, the opposite of a systemic policy that disproportionately hurts black people because of the inequalities in our society (not because of explicitly racial intent) is a systemic policy that disproportionately helps black people because of the inequalities in our society (not because of explicitly racial intent). But instead, many critical race theory-influenced polities disproportionately help black people explicitly because of racial intent, whether that black person is from a historically redlined community or a rich community in Nigeria.

In my opinion, this is one of Donald Trump’s advantages. Because his ideas are so transmissible (and lacking in nuance) in their original form, it is virtually impossible to reduce them to a more transmissible form. So while other politicians’ ideas enter the public discourse in bastardized forms, Trump’s ideas are more or less unscathed.

To a lesser extent, Bernie Sanders also used the reduction problem to his advantage in 2016. He observed that most Democratic policies will be reduced to socialism, whether or not they are in fact socialist. While Bernie Sanders’ social democratic policies may not be socialism in strict economic terms, he figured he didn’t have much to lose by just labeling his policies socialism. If he took away the “gotcha” power of the word, then people would be forced to actually engage with his ideas. And he succeeded! Socialism doesn’t have the bite in American politics that it once did.

These examples from recent history all make the case for “bulletproofing” top-level messaging. These messages should be reduced into one of their most transmissible forms. If a plausible damaging and transmissible misinterpretation exists, then simply do not spread this message! This may seem like a loss, but it is a necessary change in strategy for the digital age.

I’d like to clarify that I draw the line at misinformation. We should not be spreading “facts” that are simply false. For example, the less nuanced message “N95 masks protect the wearer from COVID” is preferable to “N95 masks protect others from COVID more than the wearer, but still protect the wearer”, but the factually incorrect message “N95 masks protect the wearer from COVID more than others” is not. The emphasis here is on the nuance / focus of the message, not the core substance.

So before you publish anything, consider the reduction problem. Are your main points particularly vulnerable to reduction? Don’t assume people will put a lot of effort into understanding your intent, because most people won’t. The best way to prevent uncharitable misinterpretation is to cut it off at the source. There will always be a place for getting into the weeds: DMs and face-to-face conversations with friends are suitable for this sort of thing. But the Internet is not that place, and our writing should match that (unfortunate) reality.